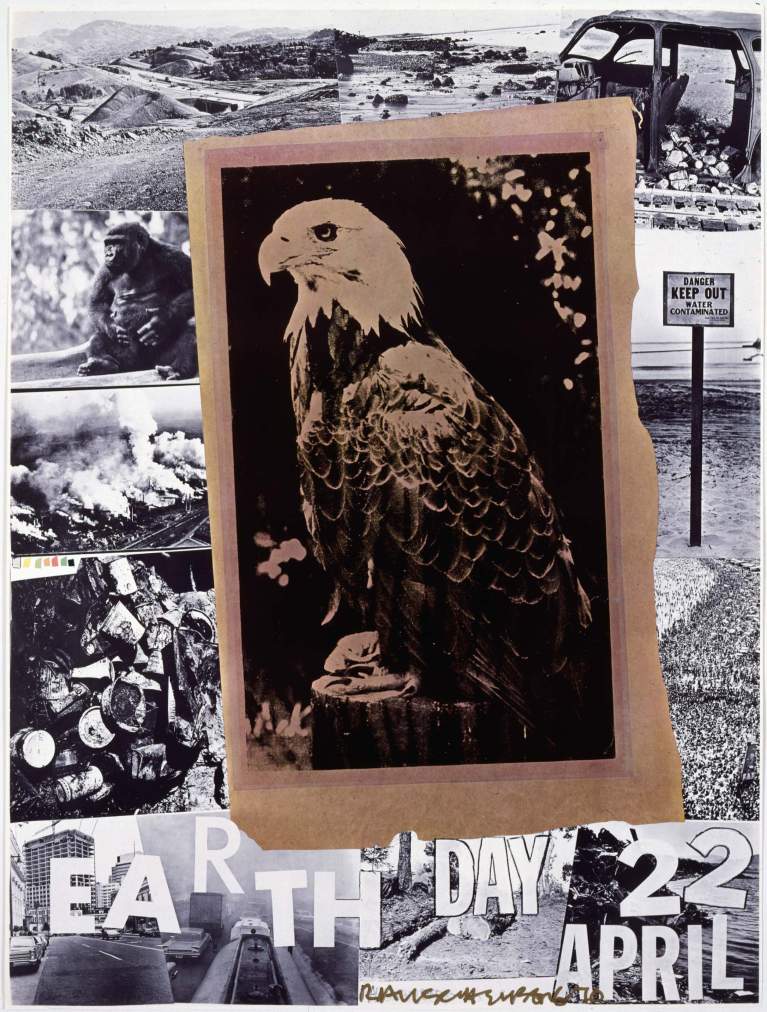

Earth Day, 1970

Earth Day

In response to a massive oil spill off the coast of Southern California in 1969, Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson initiated the idea of the first annual Earth Day on April 22, 1970. Soliciting support from Democratic and Republican leaders, Earth Day was conceived as a “national teach-in” to bring public awareness to the threat of global air and water pollution. What began as a grass-roots movement, with twenty million Americans participating, is now recognized as the launch of the environmental movement and observed in nearly 200 countries around the world.

Robert Rauschenberg designed the first Earth Day poster to benefit the American Environment Foundation in Washington, D.C., and it was published in an edition of 10,300 by Castelli Graphics, New York. Using the bald eagle as the dominant image, the artist symbolically placed the United States at the center of a global problem. Muted and muddy tones depicting environmental decay surround the national bird: polluted cities, contaminated waters, junkyards littered with debris, landscapes scarred by highways and deforestation, and the gorilla, another endangered animal. The safekeeping of the environment and the notion of individual responsibility for the welfare of life on earth was a longstanding concern of Rauschenberg, and this notion would inform his art and activism throughout his life. The poster designed for the inaugural Earth Day was one of many he would create to raise funds for the myriad social causes that were important to him.

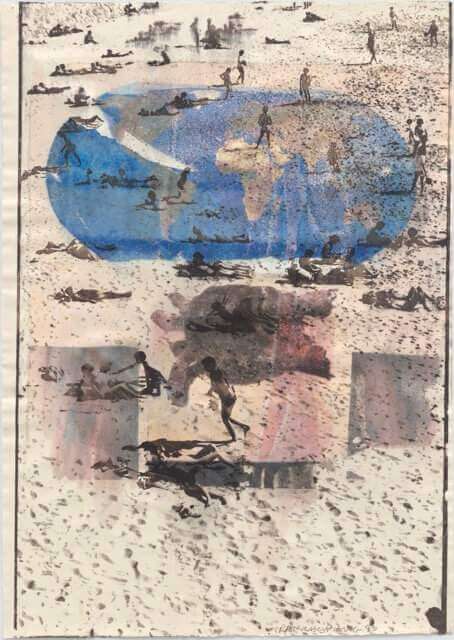

A larger format lithograph, based on the original poster design and created as an edition of 50, was published by the American Environment Foundation and produced by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles.