Robert Rauschenberg working on “Oracle” (1962-65) in his Broadway studio, 1965

Creative Synergy:

Art and Technology

1960–1971

Prior to cofounding Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) in 1966 with research-scientist Billy Klüver, engineer Fred Waldhauer, and artist Robert Whitman, Rauschenberg’s dedication to art and technology crossover can be traced to a small gadget that he made for Jean Tinguely’s Homage to New York (1960). Rauschenberg’s Money Thrower for Tinguely’s H.T.N.Y. (1960) is a plucky rare survivor of Tinguely’s monumental contraption that convulsed and combusted toward its intended demise on that frigid wet evening in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Activated by an internal gunpowder explosion, the Money Thrower’s springs popped out and launched the dozen silver dollars lodged in its coils into the crowd. With a peculiar mix of threat and generosity, Rauschenberg’s device was dubbed the mascot for Tinguely’s self-destructing machine. Rauschenberg met Klüver during preparations for the event, initiating a creative collaboration that would continue through the next decade and establishing a friendship that would last until Klüver’s death in 2004.

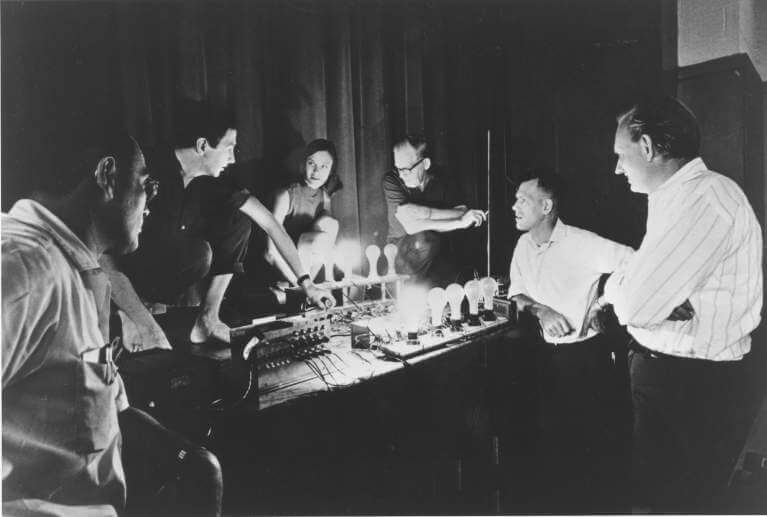

From 1962 to 1965, Rauschenberg relied on Klüver’s expertise to orchestrate Oracle, an environmental sculpture comprised of five independent units housing receivers and speakers, which were wirelessly controlled by a master unit among them (the staircase); each element emitted a separate sweep across the AM dial. Viewers could change the volume and the rate of scanning for each but could not tune into specific stations; the design emphasized abstract sound over content.

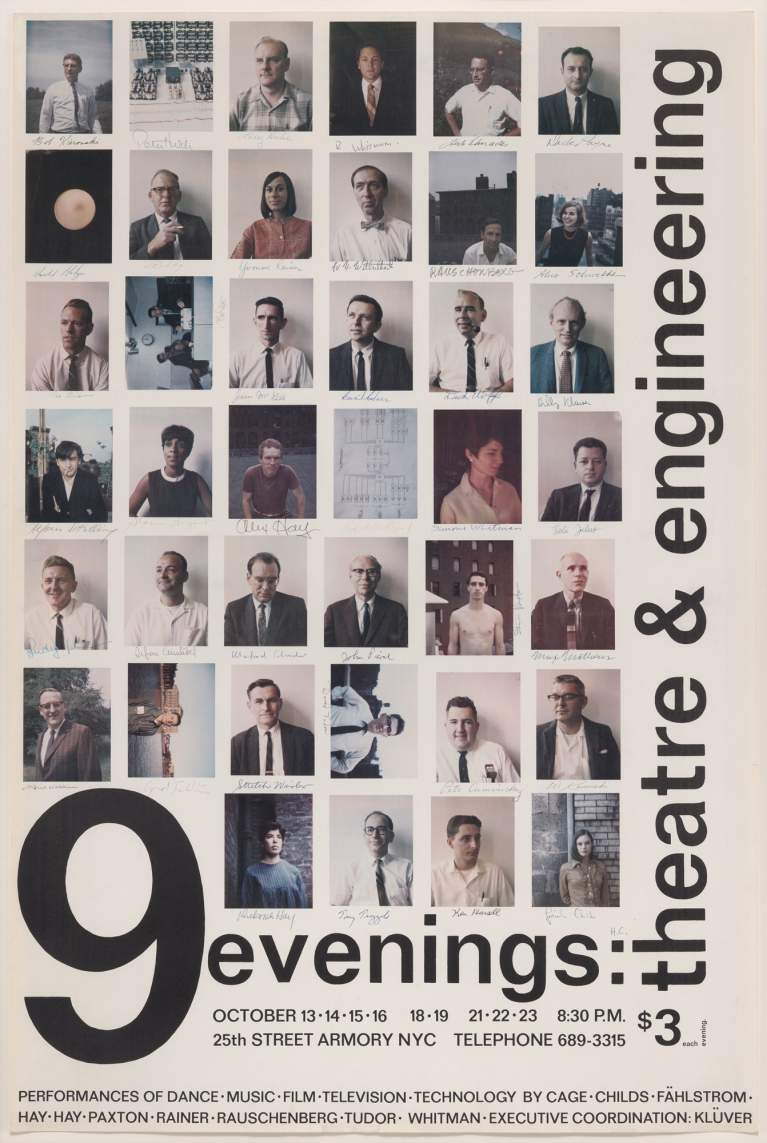

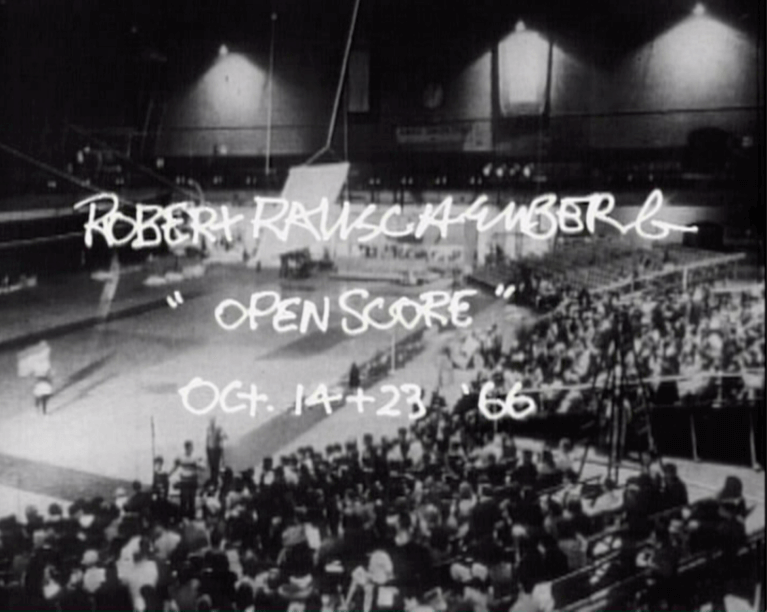

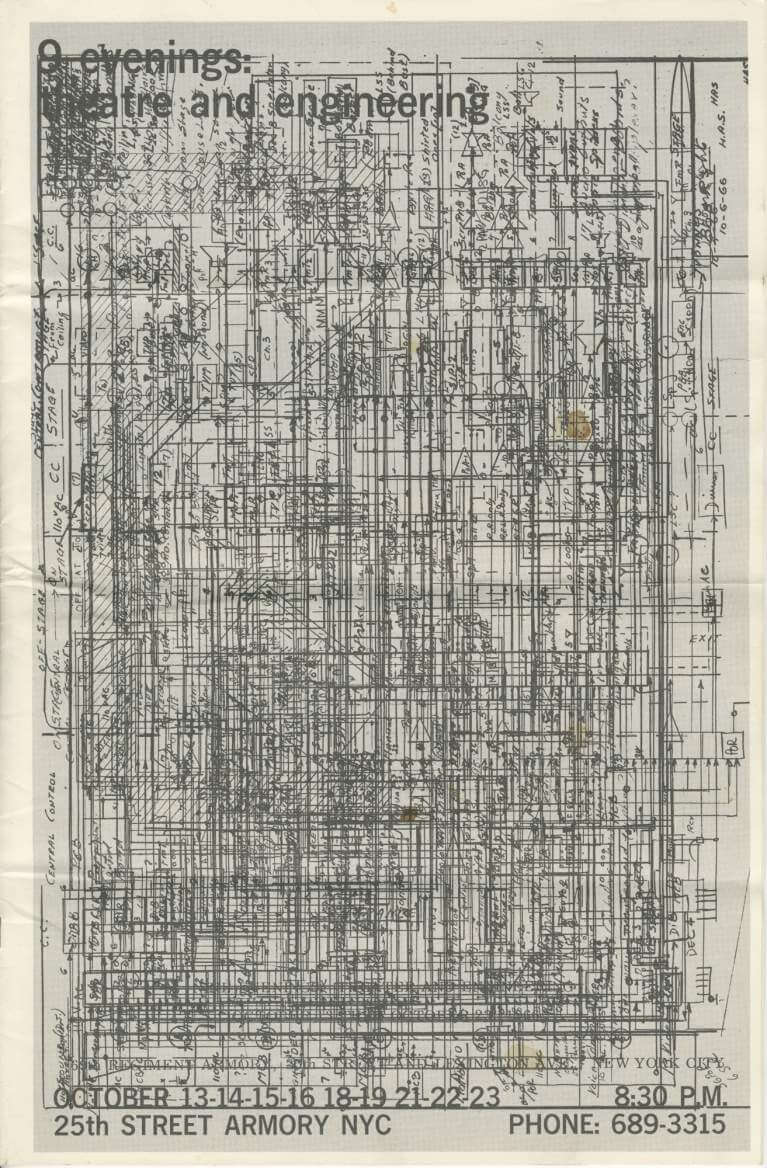

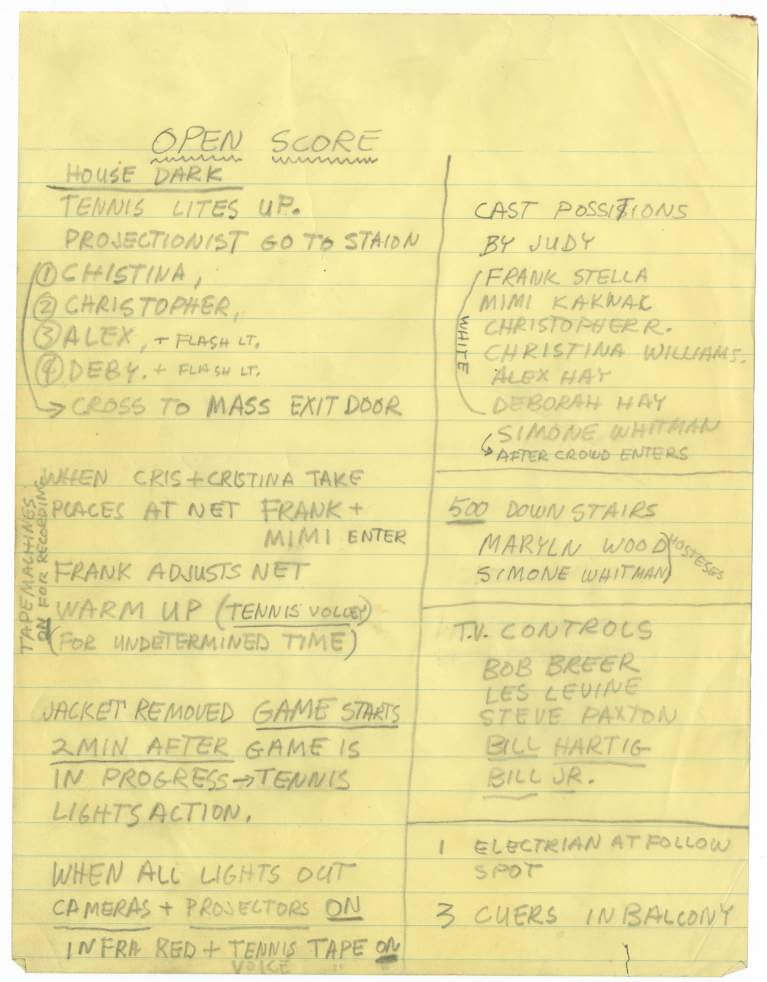

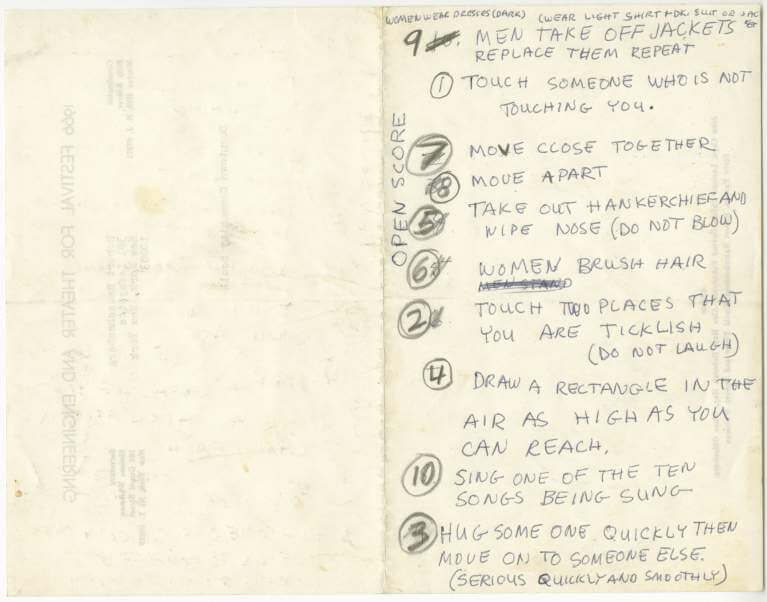

Rauschenberg and Klüver carried the spirit of art and technology integration into 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, a performance series presented at the 69th Regiment Armory, New York, in October 1966. Ten artists, including choreographers and composers, teamed up with engineers to create ten multimedia events that premiered with the trials and errors of new technology. Rauschenberg showed up every night, running errands and relaying messages when he was not busy directing his own Open Score (1966) or taking part in pieces by Öyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, and Deborah Hay. Reviews tended toward indignation (Clive Barnes, dance and theater critic for the New York Times) rather than appreciation (Jonas Mekas, experimental filmmaker and movie critic for the Village Voice). The New Yorker–writer Calvin Tomkins summed up the critical verdict that 9 Evenings was “a disaster without parallel in New York’s theatrical history.” However, historical assessments celebrate the indelible images of 9 Evenings by redeeming the then-unconsidered facets and harvesting the continual development of the ideas and propositions embedded in those cross-disciplinary collaborations.

Among other projects, Rauschenberg went on to complete three monumental technology works in concert with engineers: Solstice (1968), an interactive architectonic structure; Soundings (1968), a responsive sound-activated installation; and Mud Muse (1968–71), inspired by the “paint pots” of Yellowstone National Park, a room-sized vat of mud that is set bubbling by an internal feedback loop, which generates a duet of recorded and actual sound.