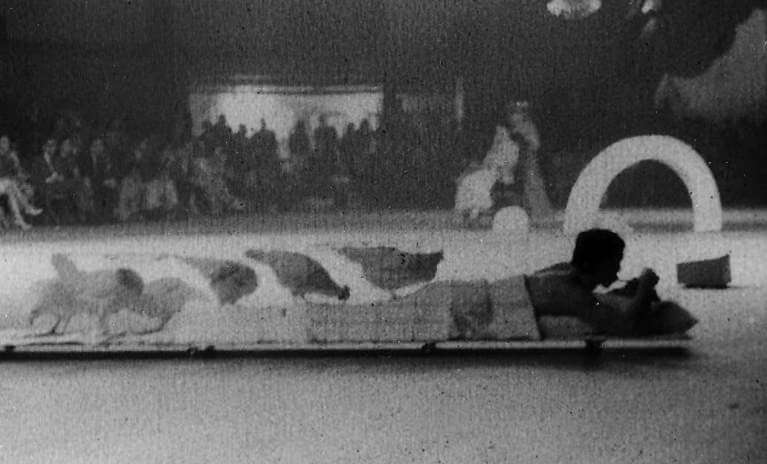

Lucinda Childs and Robert Rauschenberg with turtles in Rauschenberg’s “Spring Training” (1965) at the ONCE Again Festival, Maynard Street parking structure, University of Michigan, 1965

Rauschenberg as Choreographer

Rauschenberg’s earliest explorations of avant-garde dance and performance can be traced to his education at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, where many artists experimented with groundbreaking forms of theater. While living in New York during the 1950s, Rauschenberg pursued his interest in dance, working with choreographer Paul Taylor, providing lighting, costume, and set designs for his performances. From 1954 to 1964 Rauschenberg also served as a lighting, set, and costume designer for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, collaborating on more than twenty dances. In the early 1960s, he participated in Robert Dunn’s experimental dance workshops held at Cunningham’s New York studio (1960–62)—a course that would become the basis for the pioneering Judson Dance Theater (1962–64). It was within this context that Rauschenberg began producing his own choreographic works.

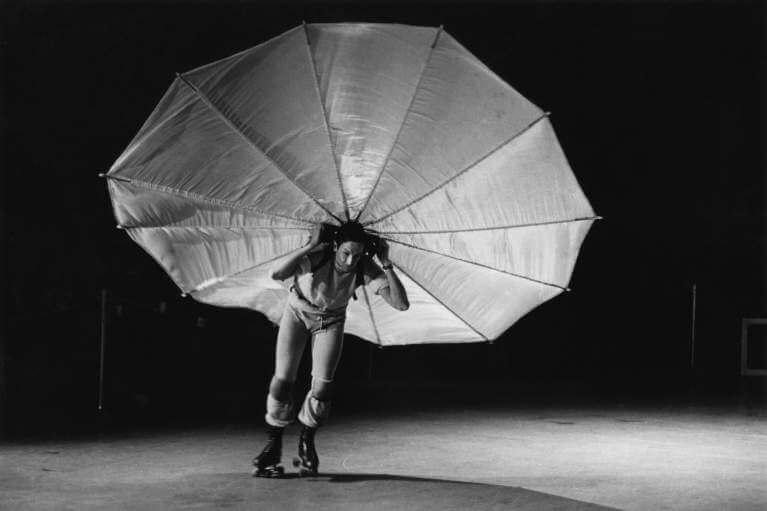

Despite his prolific dance collaborations, Rauschenberg recalls, it was not until he was “accidentally” listed as a choreographer in the press announcements for the Judson Dance Theater’s Concert of Dance Number Five on May 9, 1963, in Washington, D.C., that he would choreograph his first performance, Pelican. Rauschenberg and artist Per Olof Ultvedt performed on roller skates, Cunningham-dancer Carolyn Brown performed en pointe, and all were dressed in gray sweat suits. Rauschenberg and Ultvedt additionally wore modified parachutes attached to their backs, which functioned like decor, forming an architectural environment while simultaneously emphasizing the movements of the two skaters. Rauschenberg, who learned to skate for the performance, recounted, “Since I didn’t know much about actually making a dance, I used roller skates as a means of freedom from any kind of inhibitions that I would have.”

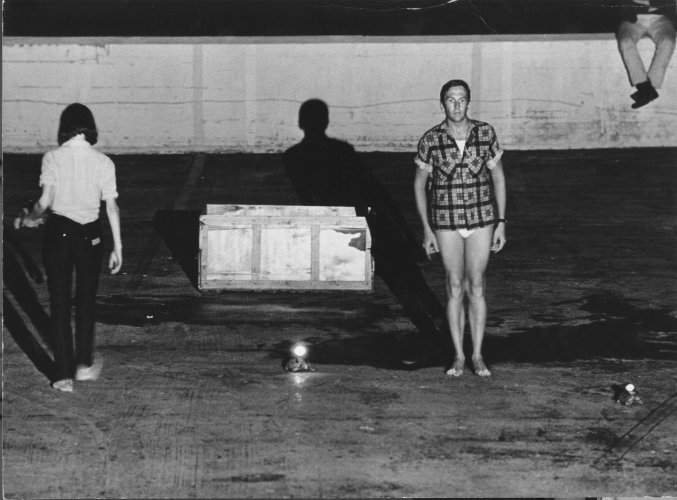

Between 1963 and 1967, Rauschenberg choreographed thirteen works, culminating with Urban Round (1967). (This number indicates all dance performances formally choreographed by Rauschenberg, including works such as Tango [1964] and N.Y. 172619 [1965].) Several Rauschenberg dances featured everyday items comprised of props, decor, or costumes, which often restricted and defined the movements of the performers. In the premiere of Linoleum (1966), for example, the actions of the dancers were largely determined by an unexpected assortment of objects: Simone Forti, wearing an antique wedding dress and holding a pot of cooked spaghetti in her lap, sat on a chair atop a mobile platform wheeled around by Deborah Hay; Steve Paxton lay in a chicken coop filled with live chickens as he ate fried chicken, periodically using his arms to maneuver around the stage; Alex Hay stood with his legs planted in an open wire bed frame, struggling to move, and his head and upper torso were covered by a papier-mâché shell. In a similarly absurdist fashion, Spring Training (1965) featured Rauschenberg on stilts, precariously navigating turtles that wandered the stage with flashlights strapped to their backs (one of which became Rauschenberg’s lifelong pet, Rocky).

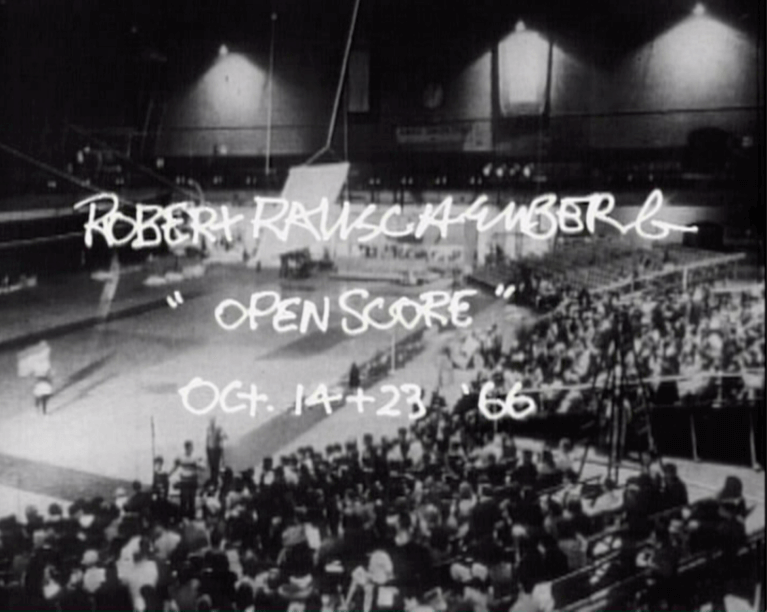

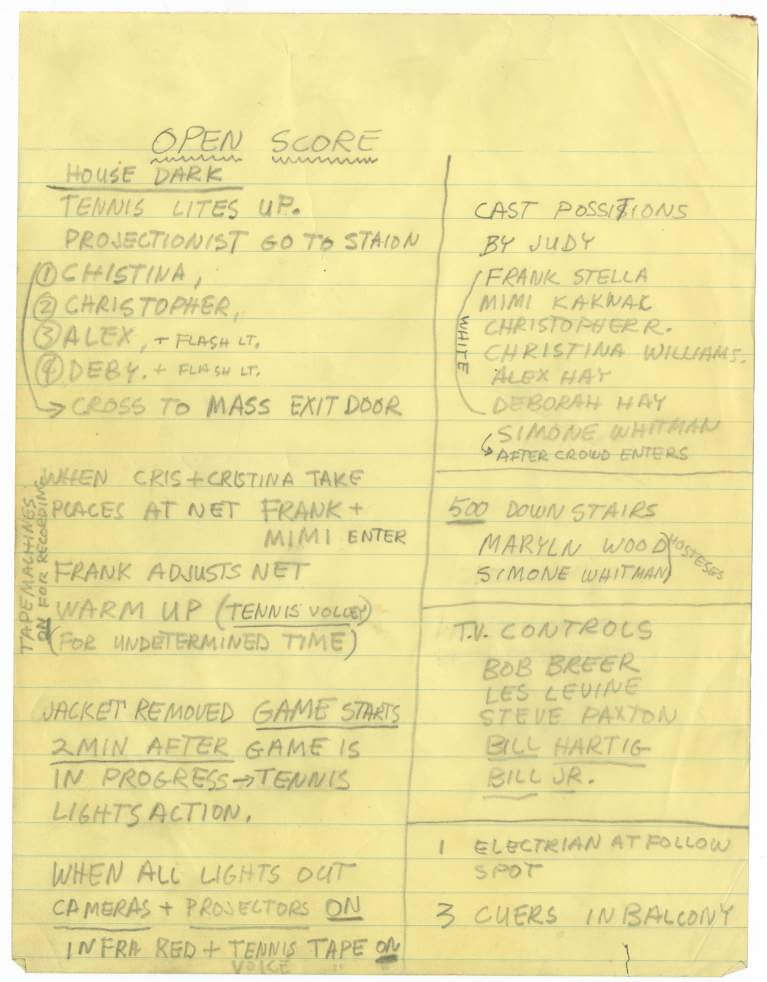

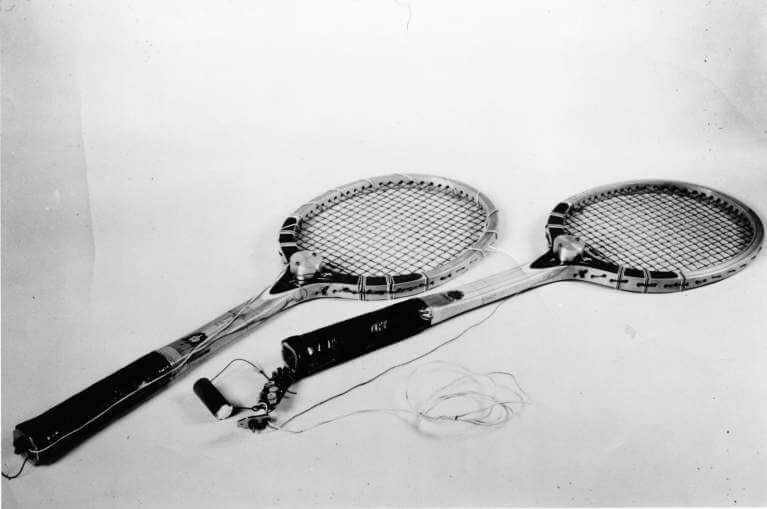

In numerous performances, Rauschenberg amplified the noises made by the interaction of performers and objects to generate unique soundtracks. In Linoleum and Open Score (1966), the artist utilized plastic suits and tennis rackets wired for sound; and in Map Room II (1965), Rauschenberg attached a microphone to a bedspring. Spring Training featured the amplified noise of Christopher Rauschenberg ripping pages from a telephone book, alarm clocks ticking in a shopping cart, and the music of a Hawaiian guitar recital. Critic John Gruen aptly described a performance as “a Rauschenberg painting come to life—one of his combines seen moving and producing shattering noises,” an effect often accentuated by the use of projected images.

Although Rauschenberg did not choreograph his own works after 1967, he continued to collaborate extensively with choreographers throughout the rest of his career.

-Jennifer Sarathy, Research Assistant, 2016