Laurence Getford

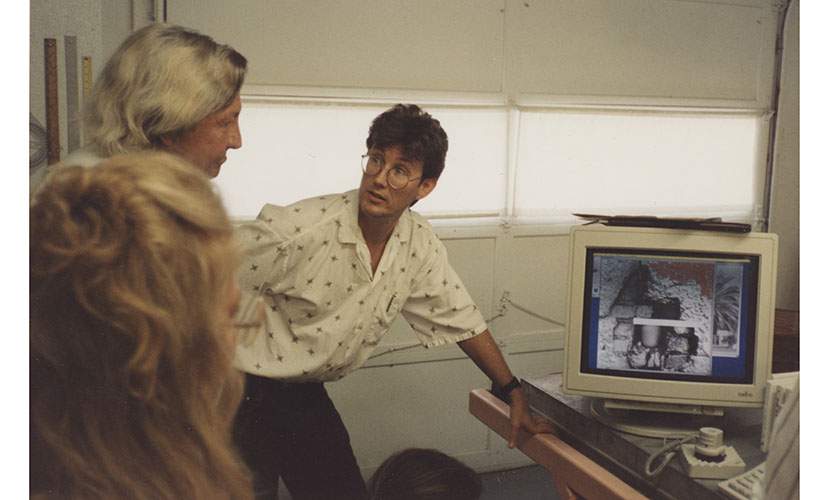

Laurence Getford is a visual artist and sound art performer who has been a pioneer in new media since the early 1970s. His work in multimedia theater attracted Rauschenberg’s attention, leading, in 1987, to a daily working relationship that spanned more than two decades. Getford researched and devised innovative techniques for digital-image processing, updating Rauschenberg’s studio with digital Iris printers in 1992. This new technology enabled a wider spectrum of chromatic possibilities, including inkjet transfers of full-color photography. These new printing techniques were instrumental to Rauschenberg’s art until his death in 2008, allowing for more saturated color transfers, as seen in numerous series including Waterworks (1992–95), Anagrams (A Pun) (1997–2002), and Runts (2006–08). Getford lives and works on an island in the Gulf of Mexico.

Excerpt from Interview with Laurence Getford by Sara Sinclair and Christine Frohnert, 2015

He did not like to look back. He really liked to move forward. He would go to great lengths to keep from retracing his steps consciously. And he was saying one of the toughest things about working with images as material, as part of your palette, is having to deal with the images of the past that come up, the emotional charges that come along with them. Sometimes he absolutely couldn’t use images that he loved—photographic images that he loved because of the associations they brought—because he was trying to keep his emotions out of the mix. And if something became too emotionally charged image-wise, he wouldn’t use it. One day I came in and a lot of images were gone, I mean hundreds. This would represent, to me, months of work and also a very large check on my chair because he knew how much extra work that this was going to make for me to replace these. He said, “I’ve just looked at those images too many times and they mean too much to me to use them anymore.” So we shredded them and threw them out.

[ . . . ] he did have this thing about the memories that images brought up and how he really did try to take that out of the work, as hard and impossible as it is. We all know how it’s just impossible to do that. If you’re dealing with something that didn’t just happen, it’s got something associated with it.

[ . . . ] What they would do is, they would have these tearing sessions. Bob had just tons of magazines that he’d subscribe to because he loved to look through magazines; he wasn’t much of a reader, he liked to look at the pictures. Well before I got there, what they did was, they built these little boxes, maybe a dozen boxes of different sizes, but most of them no bigger than a magazine page. And they would go on tearing sessions. They would just tear everything out that looked interesting from magazines and one box would be dogs, another would be trees or faces or whatever. So there were all these different categories that he had to choose from and that’s how they would choose the imagery.

So he would go over and look at the boxes, pretty much in the same way that he would look at paint if he were choosing paint. He would leaf through things and he would find four or five or whatever it took, like these two little images. Sometimes they needed to be cut down, sometimes they could be used whole, and they would get at them with the scissors or he would or someone helping him would cut the image to size as in this case. He may lay one image or paper on the press bed, but almost never just one, unless the paper would fill the whole press. He would try to fill the press with paper sheets and then start putting images down so they could run them all through at one time and make ten, twelve, fifteen prints. They were all individually designed. But he basically composed each one, but he printed it—it’s interesting and we can talk about this later too because it was an era that we went through—when he had to do all his composition backwards and I always wondered if being dyslexic helped or hurt that. Because initially when we were doing the inkjet prints, they were on opaque paper and he could not see what he was going to get at all. Except for peeking under the image after he placed it face down for the transfer. Eventually we transitioned into the transfer substrate being transparent or translucent. But when the images were opaque, it was the same process and he had to kind of look at each image and imagine what it was going to look like when it was transfer-printed.

I think he had a lot of practice doing these for what we wound up doing later with the other water process. He got really quick at it, he could—he had just a great eye and he seemed to know exactly what he wanted. He didn’t back up many times. I guess, what I’m trying to say—once he put something down, he would change occasionally, but usually the process was already done in his head by the time he got to the paper. Now when he got to these bigger pieces, that wasn’t necessarily the case. But when we were working with smaller pieces like this, that tended to happen a lot.