Lynda Benglis

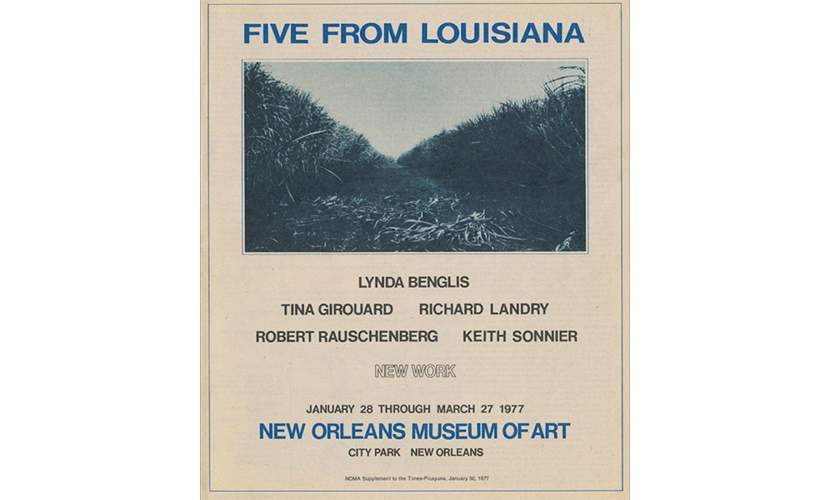

Born in Louisiana in 1941, Lynda Benglis is a world-renowned artist who has been referred to as a sculptural painter, although her artwork resists identification with any singular medium or movement. Benglis moved to New York in 1964 to pursue art. It was there that she became friends with Rauschenberg. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Benglis created works by pouring pigmented latex, spilling polyurethane foam, and dripping wax onto the floor of her studio. In the mid-70s through the 1980s she made eclectic works by molding and contorting various types of metal. Regardless of the specific medium, Benglis’s artworks are amorphous and abstract and the materials appear frozen in movement. Her reputation as a fearless feminist along with her aesthetic originality distinguished her from the male-dominated Minimalist and Process Art movements. In 1977, Benglis and Rauschenberg were included in the exhibition Five from Louisiana at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Excerpt from Interview with Lynda Benglis by Cameron Vanderscoff, 2015

Benglis: He was taking things from everywhere and it was kind of like white trash Pop. He was really a trashy artist. He found his things from everywhere, just like they all did in the beginning—but he allowed it to show. But he was a very spiffy guy and he knew how to present it. So he knew how to think; he knew how to make it into something that it wasn’t. He knew how to make trash precious. He knew how to just turn it over and make you think about it.

Vanderscoff: How do you do that, make trash precious?

Benglis: Well, ask him, because if you look at him then you can see it: that’s a Rauschenberg.

Vanderscoff: How do you think, perhaps?

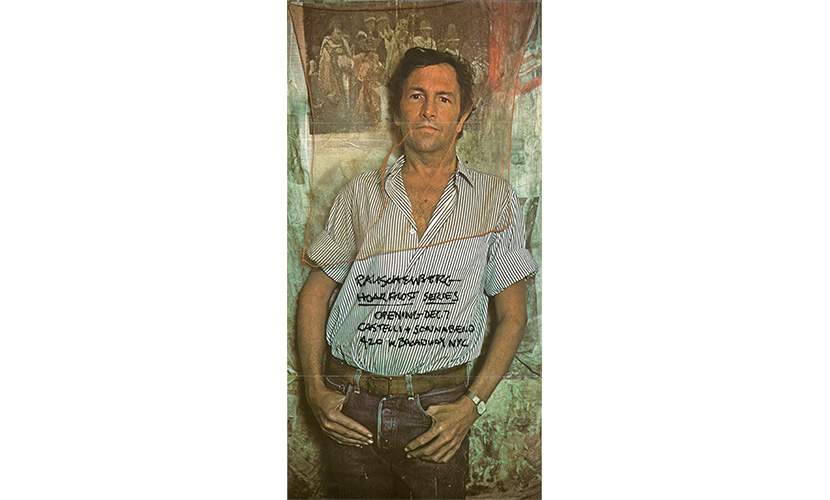

Benglis: Well, have you ever looked at his handwriting?

Vanderscoff: Yes.

Benglis: You have to figure out what—if you didn’t know his name, his handwriting in itself is pretty amazing, just the “Rauschenberg,” the way he writes his name. Only a king would write like that. You’d have to know his name before you can read it. [Laughs] It was very special, how he could turn something like calligraphy into a visual phenomenon. He could turn anything into a visual phenomenon—and it was spatial though. It was all contained or it wasn’t. It went on in an irregular way.

Vanderscoff: Right. And, of course, even initially with the Combines [1954–64], there’s that collapse of painting and sculpture and that space kind of coming out from the wall.

Benglis: That’s what I mean, the Combines, yes. But he made them work. He didn’t make them too large. Everything was in scale, human scale. And that’s the thing he always did, I think, no matter what it was, whether it was the oil, mud, sand, silt bubbling up—

Vanderscoff: The Mud Muse [1968–71].

Benglis: The Mud Muse. What finally happened with that piece, you probably know, it stayed pristine for a while, but then pretty soon people were writing graffiti all over the walls, dipping their fingers into the Mud Muse and writing whatever they wanted to say on the walls. Rauschenberg, I’m sure, loved that. Not like Carl Andre, who might present Styrofoam in the south of France in that show and the dancers decided to start walking in it and making their footprints on this white Styrofoam that was down a hill. He was inviting them to do that. Rauschenberg probably would have been amused and then done something else with it. He carried it—whatever he did, he carried to the -nth degree.

Vanderscoff: No, I follow. So you used this phrase “white trash Pop,” right.

Benglis: I just phrased it, but it is—he wouldn’t be insulted.

Vanderscoff: No, I don’t think so, but the difference between that and that neatness or that precision of Warhol, for example—

Benglis: But he is so precise. Rauschenberg was so precise.

Vanderscoff: How so?

Benglis: Well, he took both trash, our trash—all the trash essentially—and he digested it, so to speak.