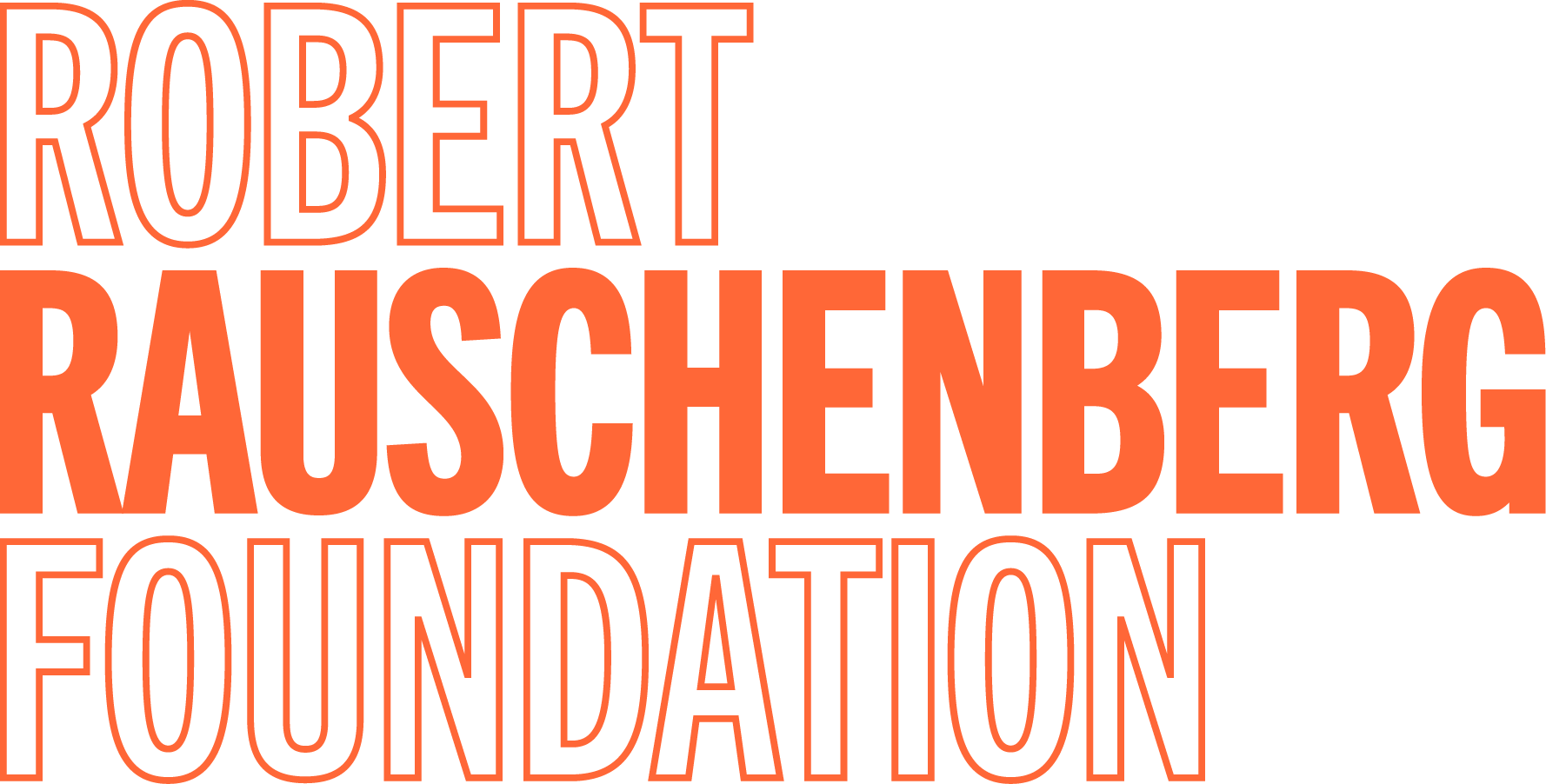

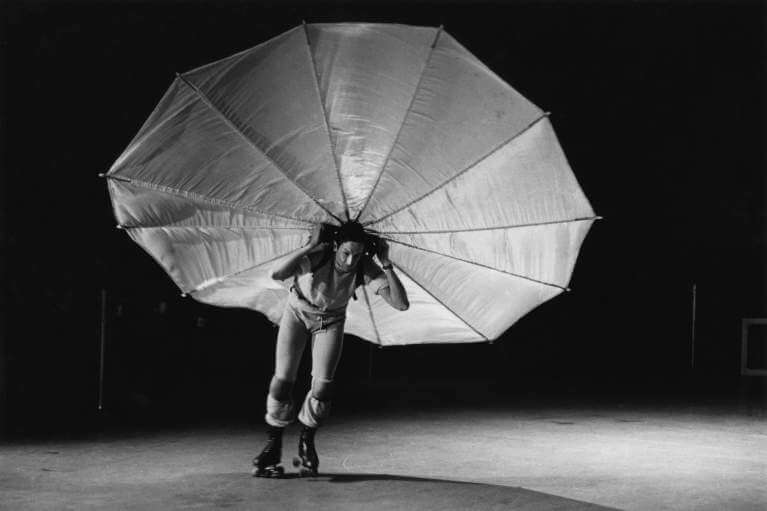

Rauschenberg performing his piece Pelican (1963), First New York Theater Rally, former CBS studio, Broadway and Eighty-first Street, New York, May 1965. Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

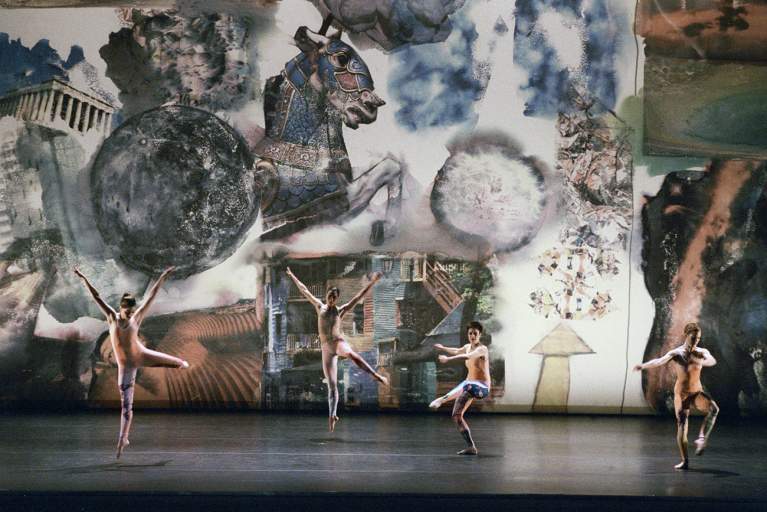

Performance, Choreography, and Stage Design, 1952–2007

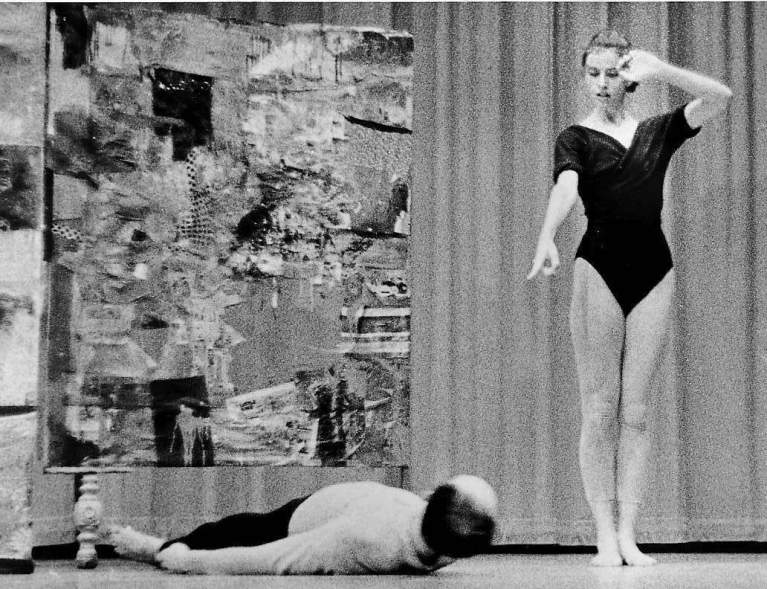

Performance, in its many manifestations, was at the core of much of Rauschenberg’s artistic output. His involvement with performance began when he participated with choreographer Merce Cunningham in composer John Cage’s Theatre Piece #1 (originally an untitled work that is sometimes referred to as the first Happening) at Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina, in 1952. Throughout his career, Rauschenberg not only designed sets, costumes, and lighting for Cunningham and other choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Paul Taylor, but he also performed and choreographed his own works. The theatrical element was not limited to live performance but was often an integral part of his nonperformance works, including the integration of sound in an Elemental Sculpture that incorporates a hidden sound; the passage of time in a Combine that includes a working clock; or the incorpation of motion in a technology piece that churns mud.

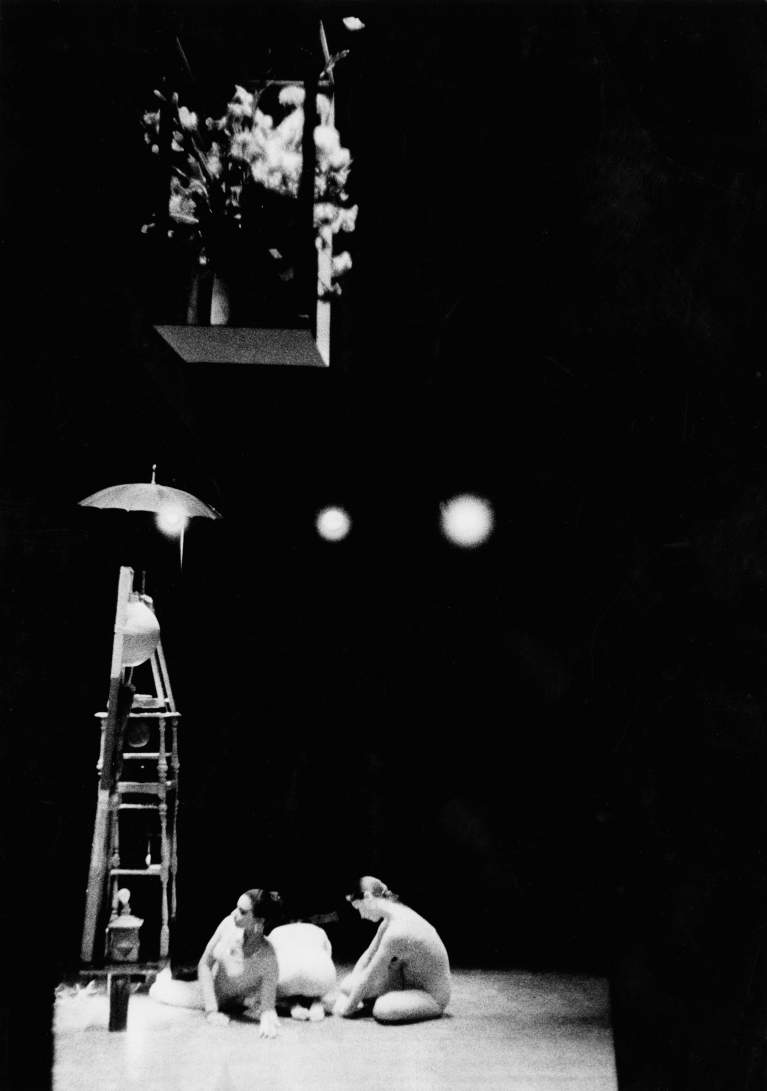

As was true of much of Rauschenberg’s work, the lines were intentionally blurred between his performance work and his work in other media. For example, a freestanding Combine, Minutiae (1954), was created as a stage set for a Cunningham performance; while his First Time Painting (1961), another Combine, was made by the artist while on stage at the American Embassy in Paris as part of the performance Homage to David Tudor. When on tour with Cunningham, Rauschenberg created scenery by spontaneously using found objects and sounds, as he developed the concept of “live décor,” or scenery generated by human activity.

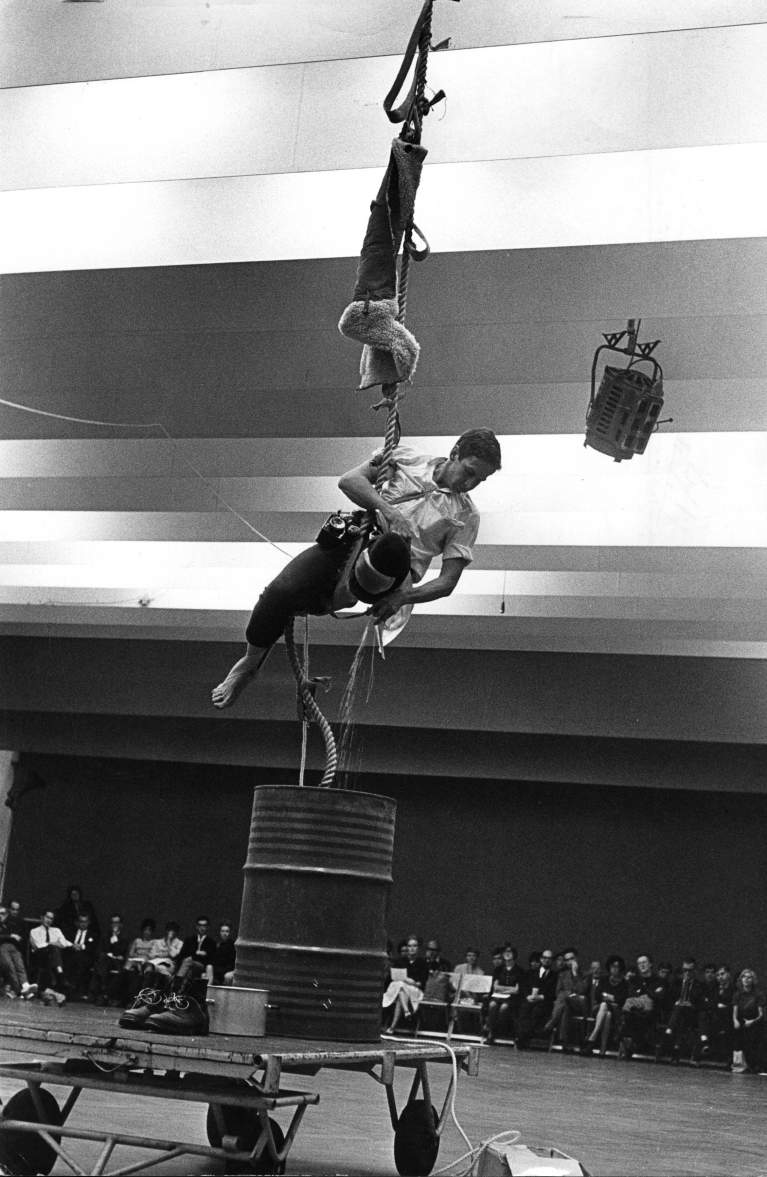

The artistic dialogue with Cage and Cunningham positioned Rauschenberg at the cutting edge of postmodern dance. His involvement in the early 1960s with Judson Dance Theater, New York, an experimental collective that included dancers as well as visual artists, resulted in performances free of narrative, emphasizing instead the purity of movement—sometimes conventionally dance-like, but also mundane movements, allowing untrained performers to participate side by side with professional dancers. Throughout his career, Rauschenberg found collaboration—either with artists working in a broad range of media and from around the globe or with engineers in the development of works that combined art and technology—to be a productive means for pushing the boundaries of conventional art making.